May 5, 2009

The critical role of parents and caregivers in the physical development of children’s brains has been highlighted in a report released by the Families Commission today.

Healthy Families, Young Minds and Developing Brains vividly demonstrates how a child’s experience of love, pleasure and security – or the lack of these – has a major impact on issues as diverse as family violence, crime, social and educational success and mental health.

Prepared by Charles and Kasia Waldegrave for the Commission, the study identifies factors that enable children to reach their full potential, or prevent them from doing so. It demonstrates that the environment children experience in their early years impacts on their young minds which, in turn, affects how well they pick up everything from language and writing to important social and moral skills such as knowing how to control their emotions and desires. They might also fail to develop empathy for others, the skill needed to understand that some actions harm other people.

Author Charles Waldegrave says: “In loving, nurturing environments the child’s brain will develop normally. But recent developments in neuroscience and child development show that ongoing experiences of neglect, abuse or violence can seriously damage development in children, leading to long term impairment of their intellectual, emotional and social functioning.”

Chief Families Commissioner Dr Jan Pryor says the study shows how important it is for governments and society to value parenting and create environments that support strong, resilient, loving families and whanau within which to raise children.

“It also highlights the importance of early intervention if things do start to go wrong for families,” Dr Pryor says. “The longer a child experiences serious deprivation, the higher the chance that this will have serious long term impacts on their functioning as an adult and the harder it will be for intervention to remedy that harm.”

The paper also discusses how the experiences of the early years impact on society, Dr Pryor says.

“For instance, the Government has signalled that it is very interested in the drivers of crime. What this research tells us is that impaired mind and brain development during childhood can be a major contributor to criminal behaviour in later life, because of the developing child’s inability to self regulate and create sensitive relationships with others.”

The Families Commission will use the study to develop advice it is preparing for the Government on the importance of early intervention, what types of intervention are needed, what works best, and where government and community family services can best target their money and efforts for best effect. The study will also contribute to the Commission’s work for easy access by parents to parenting support information, early childhood education and childcare.

Download the report: Healthy Families, Young Minds and Developing Brains

May 1, 2009

Dr Hone Kaa

Te Kahui Mana Ririki

Te Kahui Mana Ririki1 is now in its second year of operation. Our organisation is committed to eliminating Maori child abuse and maltreatment, and year one was spent focusing on establishing ourselves within the sector and securing funding for our ongoing work. We have positioned ourselves as a national Maori child advocacy organisation. Many Maori providers have asked us what this means in practice. Do we intend to speak on their behalf? Do we represent their interests?

What is becoming clear to me as we continue on our journey is that our primary role is to voice and promote the needs of Maori children and young people at a national level. This will be based on our observations of the sector, and Maori generally. And our comment will be guided by the values that underpin our strategic plan. Here are our values:

Self-determination

Primary responsibility for addressing these issues lies with Maori. Over the last twenty years Maori expertise in child maltreatment has increased exponentially. Maori practitioners are now blending generic child protection expertise with Maori models of practice. Any solutions that are developed must come from a Maori base.

We have the leadership and professional expertise in place to develop strategies to eliminate Maori child maltreatment and ensure the ongoing wellness of our ririki.

The centrality of tradition

Historical accounts indicate that Maori were kind and nurturing caregivers. This new profile of violence and abuse resonates with the experience of indigenous peoples elsewhere – it is the direct result of power-loss, poverty and cultural alienation. Answers lie in reclaiming traditions and re-constructing a violence-free culture.

Focus on Maori strengths

A combination of unbalanced media coverage, and continual exposure to negative statistics has perpetuated negative stereotypes of Maori. New strategies need to challenge these stereotypes, frame the Maori experience positively, and motivate behaviour change.

Network and collaborate

Maori services and workers are located in a whole range Maori and mainstream agencies. Any strategies that are developed need to tap into this expertise and plug any gaps that exist.

Whanaungatanga

The concept of whanau is at the core of Maori thinking. Work in Maori child health and maltreatment must strengthen and empower whanau to be violence-free. This work is not the domain of wahine only – tane and ririki must be factored into all strategies and solutions.

Educate and Communicate

These are the two main areas of activity required to achieve the changes necessary.

These principles are not new and emerged out of the Maori Child Abuse Summit Nga Mana Ririki held in Auckland in 2007. There is a subtle shift however. Despite the continuing profile of poor Maori health we no longer see ourselves as victims of something done to us. Rather we are asserting that we have the knowledge and expertise to deal with all of the most complex issues facing our people.

One of the key messages underpinning Nga Mana Ririki was:

We must stop blaming colonisation. It is time for us to take responsibility and heal.

As Maori we must see ourselves as liberated: as experts who can wrestle with any critical social issue.

Here is the profile of Maori women and family violence:

- Maori women receive higher levels of medical treatment for abuse, and experience more severe abuse than other groups of women

- Maori women between 15-24 years old are seven times more likely to be hospitalised as a result of an assault than Pakeha women

- Maori women are over represented as victims of partner abuse, more likely to report psychological abuse, to have experienced physical or sexual abuse in the last 12 months, and to have experienced more serious and repeated acts of violence (Kruger et al, 2004)

- Maori and Pacific men, and Maori women were all more likely to have experienced violent behaviours from people well known to them than men and women of other ethnic groups

- Maori are more likely than Pakeha or Pacific peoples to experience all kinds of violence

- Maori are significantly over-represented as both victims and perpetrators of violence in families/whanau

- Maori were more likely to report community violence (15%) than Pakeha (10%) or Pacific peoples (9%) and more men than women experienced this kind of violence2

And here are some facts about Maori child maltreatment:

- Maori children are four times more likely to be hospitalised as the result of deliberately inflicted physical harm

- Maori are twice as likely to experience abuse as other groups

- Rates are trending slightly downwards3

- New Zealand has the third highest rate on infanticide in the OECD, with around a third being Maori deaths

- For the period 1991-2000 child most at risk was under one year old, male and Maori4

Some Maori don’t like me talking about this context of adults hitting adults hitting children. I have been accused of blaming our people – of deficit thinking. I believe that type of comment is further evidence of the problem itself. Any social worker will tell you that healing starts when whanau begin to talk about the problem. As Maori we must begin to discuss these issues and plan our way out of the mire.

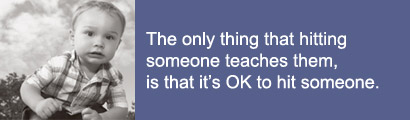

Te Kahui Mana Ririki has focused quite specifically on the relationship between parents and caregivers and ririki. This is the point where we believe we can make a real difference. Smacking is simply another expression of violence against Maori children. If we can break the habit that our whanau have of hitting children, then more serious forms of abuse and maltreatment will also reduce.

Until now the positive parenting movement has been driven by Pakeha experts. I want to acknowledge the work of Beth Wood in particular who has advocated this issue for many years, and assisted us in the development of our work.

Using Choose to Hug which was developed by organisations like the Office of the Children’s Commissioner, Barnardos and UNICEF, our Strategy Manager Helen Harte has developed a six-step approach to non-violent parenting. The six steps are:

- Stop / Kauaka: Take a breather. Calm yourself down.

- Go / Haere: Make sure your child is safe. Then walk away.

- Ignore / E aro ke: Let annoying behaviour go if everyone is safe.

- Distract / Kia whakaware: Distract them with another activity, or remove them from that place.

- Praise / Whakamihia: Be positive. Reward good behaviour with smiles, hugs and lots of praise.

- Enjoy / Kia ngahau: Use play, singing, games and toys to change behaviour.

[Note: you can download The Six Steps poster for free]

For the aficionados of non-violent parenting these six steps are nothing new. There are some subtle shifts however.

Firstly, we have taken account of the context of Maori Family Violence that surrounds the hitting and smacking of our ririki. Our parents are often grappling with their own anger management issues and the first two of the six steps deal with this. We are saying to our parents that they must deal with themselves before they deal with their ririki.

Secondly, we have taken these concepts and attached Maori words. The words are not a translation; rather they are an interpretation of these concepts. We have applied the principles from our strategic plan which I referenced at the beginning of this paper.

And finally because physical abuse is a more significant issue for Maori than other groups, rather than framing this as ‘positive parenting’ we have taken a very directive approach – Papaki Kore, No Smacking. As Maori child maltreatment reduce this approach may be modified, but feedback from focus groups we have run with Maori caregivers is that they like the clarity of the message and the six steps.

We are actually asking our people to make a major mind shift about the beliefs of parenting – away from thinking that ririki are fundamentally naughty, to thinking about ririki as intrinsically pure and perfect. So now we have prefaced the six steps with the following beliefs about ririki:

- Ririki are perfect

- Ririki have mana

- Ririki are tapu

- Ririki need warmth

- Ririki need structure

- Ririki need guidance

- Ririki grow into happy, caring adults

Once again we used existing material; in fact at least half of these principles have been distilled from Rhonda Pritchard’s book ‘Children are Unbeatable’.

Are any of these ideas new? Not really. We have gone back to our traditions as Maori, or we have simply updated existing expertise and Western knowledge.

I am certainly not intimidated by Pakeha knowledge. In fact I feel privileged because through my life in the Ministry of the Anglican Church I have been exposed to a vast body of thinking, much of it international. My philosophical base is Ngati Porou but my world view has been shaped by many other cultures and will continue to be so shaped.

In terms of Papaki Kore what is evolving is a blend of Maori and Western knowledge, which we hope will motivate Maori to transition to non-violent parenting.

Footnotes:

- Ririki is lifted from a famous Ngati Porou haka and means ‘young ones’. We use the term to describe Maori children and young people. Unlike the more commonly-used word tamariki, ririki is not gender specific.

- Pihama, L. Jenkins, K. & Middleton, A. Te Rito action area 13 literature review: family violence prevention for Maori research report, Ministry of Health, Wellington 2003.

- Ministry of Social Development, CYRAS, 2002-2003

- Doolan, M.P, Child death by homicide: an examination of incidence in New Zealand 1991-2000, Te Awatea Review 2(1) August 2004.

Tags: colonisation ,education ,family violence ,hone kaa ,maori ,maori women ,papaki kore ,ririki ,self-determination ,te kahui mana ririki ,tradition ,whanaungatanga