June 19, 2009

And another two posters for your viewing pleasure…

You’ll find more posters and free stuff on our free stuff page.

Please note: if you plan on distributing significant numbers of copies of any items from this site, please let us know so that we can include these items in our electoral return of expenses. See the notes under “Legislative requirements” in our Legal Disclaimer for more info.

Unfortunately, we don’t have the resources to post these items out to people, but you are free to download them, print them, and use them in whatever responsible way you see fit. Depending on stock levels, you may be able to get these items from your local Barnardos office.

[contact-us]

June 19, 2009

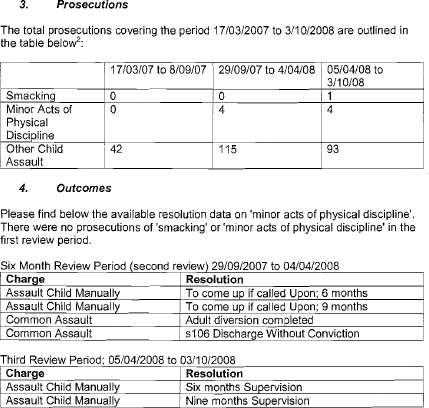

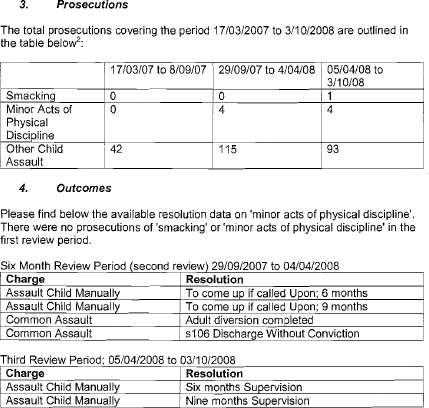

Family First are determined to prove that investigations and prosecutions in cases where there are suspicions of assaults on children are unwarranted and that good parents are being prosecuted because of the child discipline law. Unfortunately the information they give about the cases is not enough to make a judgement about whether or not action was warranted. Neither Police nor CYF will release information on cases. Media reports and court proceedings sometimes provide information but in reality few cases are getting to court. What Family First provide seem to be stories as told by people who are being investigated for ill-treatment of their children and not verified by independent assessment.

In the referendum question that Family First regards as valid the standard set for acceptable assault seems to be a “smack”. This definition does not address questions such as how hard, whether an implement was involved, on what part of the body, at what age, how often and administered by whom? These could all be relevant questions when considering whether a “smack” might compromise a child’s safety and sense of security.

Both the Police and CYF are required to investigate reports of alleged harm to a child and so they should. Any such reports could mean that the child is at risk. Whether there is further action after an investigation requires careful consideration of the facts. These facts could include type of force used, degree of force used, part of body affected, presence or otherwise of injury, age of child, circumstances of the harm inflicted, family history of violence and attitude of the adult(s) involved.

The Police data Family First claim to have obtained under OIA, most of which had already been published, unfortunately gives no detail about the kind of assaults involved. In the past Family First have defended the behaviour of parents whose actions have subsequently been found to be quite abusive. It is reasonable to assume that “smacking” and minor acts of physical discipline, refer to cases where section 59 might have been used as a defence (successfully or unsuccessfully) before law change. Even if there is a valid concern that it might have been obvious to the Police that these cases were low enough on the scale of violence not to warrant investigation nine cases is not a huge number – nothing like the flood of good parents being prosecuted we were warned by Family First to expect.

The third category used in police data is “other child assault”. This refers to more and heavy handed assaults and complex circumstances that no one could find reasonable or acceptable and are likely to have been prosecuted under the old law.

The sensible and compassionate sentences (called weak resolutions by Family First) imposed in the cases that have gone through court and been found guilty do not indicate that the judge took the matter lightly. It is more likely that judges have understanding of the need to set standards in law at the same time as avoiding unnecessary hardship on families.

In examining the details of the cases where investigations are reported to have taken place we must keep in mind the natural tendency of people accused to minimise their own wrongdoing and present their own side of the story. As previously stated verification of the stories is not provided and in any case on the face of it much of the adult behaviour reported seemed to indicate a problem existed.

The only real conclusions we can draw from the material provided by Family First is that there is interest in the community in reporting apparent ill-treatment of children which is a good thing, and that appropriate investigations are taking place.

- Family First’s police report:

June 4, 2009

Dianne DeSantis asks in The Examiner,

If a child does not know how to behave, how did they learn that behavior? Should a parent be allowed to hit a child because of the way he or she behaves?

Think about these questions. Would you be motivated to change your behavior because someone hit you? Why or why not? Would you feel violated? What makes hitting a child different than hitting an adult? What is being taught by hitting, spanking, or threatening?

The short term effect from spanking is that children will learn to avoid the behavior, avoid the parent, or how to be sure the parent does not see or learn about undesirable behaviors, but not to reason, think for themselves, or make better decisions.

The long term effects are embedded memories of either mild discomfort to pain, violent behavior, an unpleasant experience, confusion, stress, animosity among family members, unhappiness, sadness, fear, emotional reactivity, dislike for the facilitator, low self esteem, learned avoidant behaviors, and the most profound emotion attached to spanking or physical harm is anger. Many people who are taught to behave appropriately by way of spanking, threats, or physical harm become angry adults.

The whole article poses important questions about the effectiveness of physical punishment on children, and is well worth a read.

April 22, 2009

Dr Murray Straus is a Professor of Sociology and Co-Director of the Family Research Laboratory at the University of New Hampshire, and a former president of the National Council on Family Relations.

In February 2008, he gave a presentation to the American Psychological Association Summit Conference on Violence and Abuse in Interpersonal Relationship entitled Corporal Punishment of Children and Sexual Behavior Problems: results from four studies.

The studies show some interesting yet frightening results about the effects of smacking children, including

- The more smacking, the more antisocial behaviour two years later

- Smacking is related to physical aggression, psychological aggression, and property crimes

- Corporal punishment before age 12 significantly increases the probability of future verbal and physical sexual coersion

- Corporal punishment as a child significantly increases the probability of risky sex (insisting on sex without a condom and approval of violence)

- The more corporal punishment as a child, the greater the probability of risky sex as an adult

Many people who condone smacking their children say that it should only be done lovingly, but Straus’s research shows that the link between corporal punishment and masochistic sex is greatest when the parents are warm and loving.

Straus’s presentation concludes with a suggestion that birth certificates should contain a warning:

Spanking has been shown to be dangerous to your child’s health and well being.

For more information, download the presentation.

Tags: corporal punishment ,family research laboratory ,masochistic sex ,murray straus ,research ,risky sex ,sex ,sexual behaviour ,smacking ,unh ,university of new hampshire ,violence

April 19, 2009

In a study published by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in August 2008, mothers who reported that they or their partner spanked their child in the past year were nearly three times more likely to state that they also used harsher forms of punishment than those who say their child was not spanked.

Such punishments included behaviors considered physically abusive by the researchers, such as beating, burning, kicking, hitting with an object somewhere other than the buttocks, or shaking a child less than 2 years old.

“In addition, increases in the frequency of spanking are associated with increased odds of abuse, and mothers who report spanking on the buttocks with an object – such as a belt or a switch – are nine times more likely to report abuse, compared to mothers who report no spanking with an object,” said Adam J. Zolotor, M.D., the study’s lead author and an assistant professor in the department of family medicine in the UNC School of Medicine.

[kml_flashembed movie=”http://www.youtube.com/v/rPFz2n1Qt7I” width=”425″ height=”350″ wmode=”transparent” /]

April 15, 2009

There’s the thing I find difficult to understand – that any civilised person should be so upset by the idea of it being against the law to hit children that they would go to the trouble of organising a petition to parliament seeking a referendum on the issue, with the express aim of having that law overturned.

Some explanation of the mindset of the more high-profile apologists for a change in the current law is to be found in their connection with, and in some cases membership of the ACT party, the Sensible Sentencing Trust, Family First, the Destiny Church and other conservative political and religious groups. These are people who cannot see beyond punishment as a response to unacceptable behaviour whether in the family or society at large. Their field of vision ranges from hitting naughty children to locking up violent offenders and throwing away the key. Neither response has ever been effective in improving children’s behaviour or in deterring violent crime. Quite the reverse.

Equally concerning is the willingness of these groups to dishonestly manipulate public opinion. The 1999 Law and Order Referendum, initiated by the Sensible Sentencing Trust, provided a striking example of the ‘Have you stopped beating your wife?’ style of survey and was deliberately designed to offer respondents Hobson’s choice. It read:

Should there be a reform of the justice system placing greater emphasis on the needs of victims, providing restitution and compensation for them and imposing minimum sentences and hard labour for all serious violent offences?

Three questions but only one available answer – either Yes or No. So if you were in favour of ‘greater emphasis on the needs of victims’ and ‘providing restitution and compensation for them’ – as I am – you also had to be in favour of ‘minimum sentences’ and the brutal Victorian concept of ‘hard labour’ for all serious violent offences’. Which, needless to say, I am not in favour of.

Ninety-two percent of respondents apparently were. But most thinking people would have realised that the referendum presented impossibly conflicting options within the one question and would not have responded at all.

In an interview I did with the Sensible Sentencing founder on Radio Live a couple of years ago, Garth McVicar agreed that the Law and Order Referendum question was so flawed as to be meaningless. One might have thought the advocates of smacking – essentially the same people – would have taken care to ensure that the same mistake would not be repeated.

But the ‘Anti-Smacking Referendum’ has again been deliberately phrased to bamboozle respondents. It reads:

Should a smack as part of good parental correction be a criminal offence in New Zealand?

This is the equivalent of asking: ‘Should doctors recommend an exclusive diet of McDonalds and KFC as part of a healthy weight loss programme?’ McDonalds and KFC cannot be part of a healthy weight loss programme. And it is open to serious doubt whether smacking can be part of ‘good parental correction’.

If they are to have any validity at all, the language of referenda questions must be neutral. To make the ‘Anti-Smacking Referendum’ neutral, the word ‘good’ has to be deleted from the question. Even its title is misleading since there is no reference at all to ’smacking’ in the Act. The word simply does not appear.

Bradford’s bill was designed to prevent abusive parents using Section 59 of the Crimes Act to escape penalty. Its purpose was clear:

To abolish the use of reasonable force by parents as justification for disciplining children.

The wording of the current Act reflects this:

Nothing in the Act or in any rule of common law justifies the use of force for the purpose of correction.

And it includes the following clarification:

To avoid doubt it is affirmed that police have the discretion not to prosecute complaints against a parent of a child, or person in the place of a parent of a child, in relation to an offence involving the use of force against a child where the offence is considered to be so inconsequential that there is no public interest in proceeding with a prosecution.

That is precisely what the police have done.

Well, in the end it comes down to whether or not you think it should be legal to hit children. ‘Smack’ is such an innocuous word. But you cannot ’smack’ a child without ‘hitting’ or ’striking’ the child. And the word includes a range of possibilities – from the ‘tap on the bum’ which the proponents of the referendum would have us believe a smack means, to the volley of frenzied thumps which most of us have observed from frazzled parents on the street, in supermarkets and on buses. Indeed, one of the best arguments against smacking is watching a parent smack a child. Generally the child is squirming or struggling to get free. The parent restrains the child by holding onto its arm with one hand, while using the other hand to paddle its bottom. Usually the child is crying or screaming. It is not an edifying sight.

But it is instructive. Smacking invariably means that the parent has lost control. Reasoning and constructive communication have been abandoned in favour of physical force.

I suspect most parents feel bad after they have hit their child. And, as a parent of five children and grandfather of ten, I understand very well the stresses that can impel the most loving father or mother to strike out. We should be careful, as the Act allows, not to prosecute the parent who on a rare occasion lightly smacks a misbehaving child.

But that is very different from the state legitimising or sanctioning the smacking, hitting, striking, corporal punishment – whatever synonym you prefer – of children by their parents. That is a very slippery slope. Proponents of a change to the law want a ‘light slap’ to be legal, but the term defies definition and the police and the courts will be faced with the same impossible task they faced in defining ‘reasonable force’.

At present children are protected in law from all corporal punishment in 24 countries. They include Spain, Italy, Greece, the Netherlands, Hungary, Austria, Germany, Denmark, Israel, Norway, Finland, Sweden – and New Zealand.

We should be proud to be on that list.

—

The original article can be found on Brian Edwards’ blog, where you can join the discussion.