Posts Tagged physical discipline

August 7, 2009

Terry Dobbs wrote an insightful piece in today’s Herald, discussing the results of her research and its implications for improving behaviour outcomes for our children. Here are some excerpts:

Proponents of smacking argue it is not child abuse and that smacking and child abuse are not related issues. They claim that physical punishment is only used as a last resort, that smacking is lightly administered and harmless and should be used when a parent is calm and loving.

But how real is this – what do children tell us? In 2005, as part of her Master’s thesis at Otago University, she interviewed 80 children aged between 5 and 14 years old about their experiences and understanding of family discipline. They were from ordinary New Zealand households with no history of child abuse or neglect.

Some 91 per cent of children in the study said they had been physically punished.

Adults may define a smack as something a lot gentler than a hit, but children were clear that a smack is a hard hit that hurts both emotionally and physically.

Fear and pain may sometimes achieve short-term obedience, but in the long term these emotions are unlikely to contribute to positive behavioural outcomes or promote children’s effective learning.

Many of the children believed smacking did not work as a disciplinary tool. They said that the use of time out, having privileges removed or being grounded were far more effective means of discipline.

The children’s responses render many adults’ claims and justifications highly suspect. It is also concerning that quite large numbers of children reported adult behaviour that was in fact abusive.

[Progressing to more effective discipline techniques means] moving on from a number of deeply held and understandable attitudes and emotions – coming to terms with the fact that your own loving parents hit you (they knew no better), that you may have harmed your child’s development (it’s never too late to change that) and that the law can be regarded as a positive move for children rather than an unwelcome imposition on adults.

Our 2007 child discipline law is only two years old – let’s give it time to help New Zealand grow happy, healthy children.

Read the whole article.

Also see a copy of the report “Insights”, which describes the results of Terry Dobbs’s work, and was commissioned by Save the Children

August 5, 2009

Open Parachute has a cogent summary of the recent Police Statistics on the Child Discipline Law.

1: “Smacking” in itself is not an offence. The report had to consider offence codes which weren’t “smacking” but most likely to include “smacking” type incidents.

2: The legislation has had “minimal impact on police activity.”

3: During the review period “police attended 279 child assault events, 39 involved ‘minor acts of physical discipline’ and 8 involved smacking.”

4: There has been a decrease in ‘smacking events’ and ‘minor acts of physical discipline.’

5: There has been an increase (36) of ‘other child assault’ events. (We should be concerned about these).

6: “No prosecutions were made for ‘smacking’ events during this period.”

Read the whole article at Open Parachute.

July 24, 2009

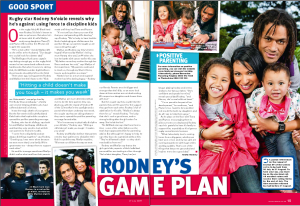

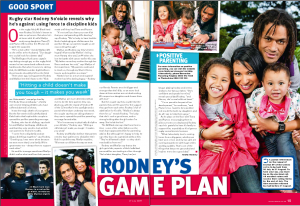

In an article in this week’s NZ Women’s Weekly, All Black and Wellington Hurricanes captain Rodney So’oialo speaks out in support of positive parenting and the current Child Discipline Law.

Rodney says, “It isn’t necessary to physically discipline your children… Hitting a child doesn’t make you tough, it makes you weak.”

Read the entire article. Thanks to Rodney and the NZ Women’s Weekly!

June 26, 2009

By Deborah Coddington

Why am I supporting the Yes Vote Team? For a number of reasons.

First, there’s the pragmatic reason.

Ten years ago I didn’t think much about Section 59 of the Crimes Act, but then I was assigned to write a feature for North & South magazine on the short life and cruel death of James Whakaruru. I interviewed the families of James and his killer and I realised, to my horror, that it wasn’t just a “light smack” used as everyday discipline, but jug cords, vacuum cleaner pipes, belts, closed fists, pieces of wood – anything close at hand when tempers were lost.

Members of the whanau argued with me, even as the earth on James’ grave was still fresh and the little windmills fluttered in the Hawke’s Bay breeze, this was acceptable if their children were naughty. Misbehaviour was defined as not eating their food, answering back or not answering back depending on the mood of the parent, making a mess – in fact any behaviour seemed to depend on what side of bed the parents got out of.

With some people you can educate and persuade as much as you like but you’re never going to make a difference. I believe you have to accept that laws must be changed if children’s lives are to made better. I accept that children will still die – sadly – and children will still be bashed, but there will be parents whose behaviour will be moderated because it is against the law to smack, belt, slap or whatever you like to call it.

You only have to look at smoking laws, or seatbelt laws, to see how they have changed people’s habits.

Secondly, the philosophical reason. I believe in the non-initiation of force, so why shouldn’t that apply to children as well as adults? Why should children have a lesser defence in court when they have suffered violence?

If I give my husband a shove, or a flick over the ear, or even a smack on the bottom, that is assault. There is no defence. If he lays a complaint and it goes to court, I cannot use “reasonable force” as defence because my husband might have come home late from the pub for the fifth time that week and needed some discipline.

So why should a child, who may have suffered similar initiation of force against their person, not be similarly protected? A child is a human being, with the same powers of reason as an adult – a mind, a heart, a brain. A child is not an “almost human being”.

Thirdly, getting rid of Nanny State. Eh?

Yes, you read that correctly, I want Nanny State out of our lives. Therefore the same law should apply to adults and children (though I am happy with the John Key amendment as it stands).

The pro-smackers who claim Nanny State is telling parents how to raise their children by banning smacking are actually doing more of the same by telling parents what kind of smack they can give their children. Act MP John Boscawen wants a new Bill which would allow a light smack. This is just another politician butting in with another law. Sue Bradford’s Bill actually got Nanny State out of people’s lives, but there was so much hysteria, nobody seemed to realise that.

I don’t expect miracles from Sue Bradford’s law change but hopefully, in the next few decades, we might see a shift in attitudes toward children in this country. It doesn’t help when issues are poisoned, and people like Christine Rankin are applauded for polarising the debate. It’s not simply a case of leftie versus rightie; Commie versus Christian. Jesus said suffer the little children to come to me, but Family First backs a father who allegedly repeatedly pushed over his little boy on the rugby field.

Loving smack? No such thing. How about hateful hug? And finally, consider this. Within marriage, rape was once legal between man and wife because marriage was taken as consent. Imagine we were campaigning to change the law, and those who opposed the amendment had written a referendum question which asked: “Should forced sex as part of a good marriage be a criminal act?”

June 24, 2009

KERRY WILLIAMSON on his Dominion Post blog, says he would like to think that he will never smack his new-born baby boy – ever.

“No matter how mad I get when he acts up, I just don’t want to be that kind of parent. No matter how loud he screams, no matter how big a tantrum he throws, and no matter how much he ignores me, I don’t want to smack him,” he writes.

He’s also annoyed that the government has legislated to this effect saying: “I’d like to think that parents should be able to parent however they want. I’d like to think that parents are responsible, caring and considerate towards their children. I can’t imagine that not being the case. “

However, he says, the reality is not so nice nor easy and goes on to cite numerous and terrible cases of child cruelty in New Zealand meted out by parents who believe in physical punishment.

June 10, 2009

In early 2006, in the epilogue of the book, Unreasonable Force: New Zealand’s journey towards banning physical punishment of children, I said:

Despite the years of debate about the place of physical punishment in child rearing there are still some people who fear or even resent the law change. However, I believe that it will not be long before the vast majority of people in our country will feel confident that Parliament did children a great service in 2007.

I still believe this strongly. I am confident that despite the upcoming referendum, and whatever its non-binding outcome may be, children in this country are benefiting from a move away from the use of physical discipline.

Over time this will result in many more children having safe and positive childhoods and fewer adults regarding the use of violence as a right.

Individuals and organisations who oppose the law change hope that the referendum outcome will lead to the reintroduction of a statutory defence so that parents can be confident they are within the law when they smack, whack or hit their children. These people believe that a smack is part of good parental correction. It’s not of course.

Any reversal of the law would be saying to New Zealanders that it is a good thing to smack your child. Some parents will believe that if one smack does not work let’s do it harder and more often. And what will the children be learning when they are smacked?

I reckon the messages they will take on board are things like: “The person I trust and love wants to hurt me” and “When you are very angry with someone you should hit them”.

There are other messages that a reversal of the 2007 law would symbolise as well. For example, it would tell us that children are not entitled to the same protection from assaults that adults enjoy, and that while society has come a long way from the days when we condoned wife beating as standard practice in the home, a return to state sanctioned child beating would be fine.

I believe the new law is working well. Parents are not being prosecuted for minor assaults.

The section 59 law change was never about punishing parents. It was about influencing attitudes positively and I believe this is happening. Many parents, grandparents and others now have a healthy interest in learning about alternatives to physical discipline.

The upcoming referendum will no doubt be accompanied by familiar arguments.

For example, some of our opponents say that the law change has not led to a change in behaviour and that it has not led to a reduction in child abuse.

I have no idea what these claims are based on. The section 59 law change was never going to immediately address serious child battering or murder – how could it?. Laws in themselves to not stop people committing crimes – individual and societal attitudes do.

All we could ever hope to do with the section 59 amendment was to level the playing field by removing the ‘reasonable force’ defence for physical punishment, and work towards a gradual change in attitudes throughout society, aiming for a time when people will no longer see beating or smacking children as either desirable or acceptable.

Beliefs about the use of physical punishment are one factor in child abuse. Of course there are others – like poverty, poor housing, drug and alcohol abuse, physical and mental illness and intergenerational family violence, which can all be contributory factors.

But violence and abuse can happen in the wealthiest of families, and attitudes about hitting children are a key part of the equation wherever you look. It is the underpinning acceptance of violence against children that we have to keep changing, both through the law change and with more and improved parent information and support.

I welcome the opportunity the referendum gives us to remind ourselves about the responsibilities of nurturing children, of raising them in violence free homes, and of finding ways to guide their behaviour that enhance self esteem and the development of self responsibility.

I encourage anyone reading this to vote Yes for Children, to vote Yes to keep the law change so many of us have worked for over many years.

June 10, 2009

TVNZ has posted Laila Harre’s reaction to the Jimmy Mason case on their web site.

She says:

The law is being used to bring people to account for child assault. Under the previous law, parents could use the defence of “reasonable force” to correct the child. Juries were often convinced that quite vicious attacks on children were reasonable force. We needed change the law to protect children from being punched in the face. We’ve done that, a jury has convicted.

The judge will now have an opportunity to consider a sentence; the judge has indicated that he’s likely to get a non-custodial sentence. He won’t be sent to prison, he’ll be sent to some kind of anger management class, and that’s exactly what this guy needs. He needs advice on parenting without using physical discipline. I think that this case is a timely reminder – it used to be acceptable to do this sort of thing, and it no longer is.

Watch the video!

May 26, 2009

As the referendum campaign heats up, supporters will have seen a number of claims being made about the Child Discipline Law and the Yes Vote coalition. We decided to put the record straight.

May 18, 2009

In Support of the ‘Yes Vote’ for the NZ Referendum on Child Discipline 2009

Lauren Porter

The intention of most parents who use physical discipline is to correct behaviour and help their children become people who will make good choices, manage their actions, relate well to others and refrain from harming, destroying or upsetting the environment and people around them. In other words, their intentions are based in caring about their children.

The smacking issue, then, is not one of good versus bad parents. Nor is it one of ‘good’ use of physical discipline versus ‘harmful’ use of physical discipline. As with most issues affecting child development, this issue must be seen through the eyes of the child, and with a critical look at how smacking can interfere with the creation of healthy parent-child relationships and the adult relationships in that child’s future.

Many decades of research in the fields of attachment theory, neuroscience, child development and infant mental health have taught us that a healthy parent-child relationship is built on sensitivity and responsiveness, a foundation that allows the parent to come to know the child for who she really is and for the child to come to know herself – and her parent – within a safe and loving environment. A cornerstone of this process is called regulation. Basically, regulation is the ability for us to recognise our feelings, make sense of them and manage them. This is not only a key to the parent-child relationship, but to all mental health.

Children learn to regulate their feelings through interaction with their parents and other caregivers. These ‘co-created states’ allow a calm and loving adult to help the child learn the regulation ropes. For example, when a loud noise startles an infant and he begins to cry, most parents reflexively pick up the baby and give him a cuddle, usually speaking in soft soothing tones. This demonstrates how parents who have never heard of the word ‘regulation’ simply know that a young baby is unable to regulate himself. He needs help to calm down and when he is very young we must do the bulk of the work for him.

Imagine teaching a child to dance. At first they may stand on your feet, holding your hands and getting the feel of how their body moves. Later, as they get more comfortable, they can stand beside you on the floor, watching your feet but doing the steps themselves. Finally, after many lessons and much time, they will dance on their own whether or not you are in the room. But if the music changes they may again need a lesson to learn new steps and increase their repertoire. Eventually they will have dancing in their bones, knowing how to move with each piece of music they hear.

Teaching a child regulation is the same process. At first we do it for them, then with them, then they learn to do it on their own. But this takes a few years at least and even then when the going gets tough they need our help. We are no different – when adults go through crises we need loved ones to lean on to help us manage and get through.

A healthy attachment relationship teaches regulation with each step. When a baby succumbs to frustration or fear, when a toddler veers toward a meltdown, when an exhausted child reaches tears, the parent is there to comfort and teach. The teaching isn’t explicit. It comes from within the trusting relationship, from within the unspoken knowledge that the parent knows how to be calm and can model this for the child.

When a parent – regardless of how well intentioned – adds the ingredient of physical discipline to the relationship they unintentionally add fear to the equation. Fear is the key feature of disorganised attachment. In this most-worrying attachment style, the relationship is overshadowed by the child’s association of fear with the parent. This puts the child in an impossible situation: the person they love most is also a person to be feared. This impedes the ability to fully trust, to be vulnerable, to be emotionally present.

As you can imagine, this means that learning regulation is near-impossible. Not only can the child not feel safety and trust that allows this emotional learning, but the parent is regularly demonstrating that they do not have the regulation skills to teach. A parent who is angry or hitting is not a model of healthy regulation.

It is no surprise that attachment and psychological research show that children who experience physical discipline have higher levels of aggression, disobedience, anxiety, depression and addiction, as well as insecure attachment. Their ability to learn to manage their feelings and their ability to form a consistently warm and loving relationship with their parent has been impaired.

It is critical to remember that the rewards-and-punishments paradigm of behaviour management was invented by psychologist BF Skinner and his colleagues in the 1930’s and 1940’s. They learned – through work with rats and pigeons – that by rewarding certain behaviours and punishing others you could create ‘operant conditioning.’ In other words, you could train an animal (or child) to do certain things and not do other things via this method. Skinner became quite famous and this methodology, which still lingers in our culture today, was embraced by many. Behaviourism was not and is not concerned with anything other than training a being toward particular ways of acting. It omits deeper concerns like the effects on relationships, on mental health, on the development of compassion and empathy.

Neuroscience and attachment offer a solution. Empathy is learned through loving regulating relationships beginning in infancy and lasting through childhood and beyond. If we as a society want to develop something more – something that includes the ability to teach and learn empathy – we must forgive ourselves for our mistakes, let go of outdated ways of thinking, and embrace a new way of being with our children.

—

Lauren Porter is a principal at the Centre for Attachment. She is a member of the External Advisory Group for the NZ Government Taskforce on Child Maltreatment, a member of the Attachment Parenting International Research Group (API-RG) and an Infant Mental Health Association Aotearoa New Zealand (IMHAANZ) Executive Committee. She is the mother of two children.

Tags: attachment ,attachment theory ,centre for attachment ,child development ,empathy ,lauren porter ,mental health ,neuroscience ,physical discipline ,regulation ,skinner

April 17, 2009

Physical violence as a form of discipline is standard for most cultures around the world. Many Muslim parents are in the habit of using physical punishment, sometimes of a severe nature. This is despite there being no verse in the Qur’an requiring or even condoning the physical discipline of children. Neither is there any instance of Muhammad ever striking a child. He never used violence as a form of discipline on his own children or grandchildren.

There are some instances where physical punishment is allowed, for example to ensure that a child completes the daily prayers. In this example, physical discipline can only be used as a last resort for children of 10 years or older.

Even the most conservative scholars agree that a child should not be struck in anger. There is a strong requirement in Islam to show love and mercy towards children, and to preserve their dignity – this is just as much a right of the child as the right to be fed, clothed, and educated. One of my favourite stories is this one:

Abu Hurairah reported: The Prophet (Muhammad) kissed his grandson Al-Hasan bin `Ali in the presence of Al-Aqra` bin Habis. Thereupon he (Al-Aqra` bin Habis) remarked: “I have ten children and I have never kissed any one of them.” The Messenger of Allah (Muhammad) looked at him and said, “He who does not show mercy to others will not be shown mercy”.

From my own experience, I have never seen a child hit or smacked in an absence of anger. I’ve never seen or experienced a parent who has sat down with the child, explained what was done wrong in a loving manner, and then smacked the child with love. I’m not saying it never happens, but that I haven’t seen it. Smacking has either been a response of the moment as a result of anger or a calculated attempt to instill fear.

Fear as a method of raising children is effective in that it limits behaviour and enforces compliance. The consequence is that this fear damages the relationship between child and parent. Children are unlikely to confide their troubles to parents who they fear. A parent should not be resorting to fear, but to respect and love. The best form of discipline is, of course, being an example yourself of the kind of conduct you wish to inspire in your children.

Given this background, I had no problem with the 2007 changes to Section 59. I don’t believe it criminalised parents who smack their children, but rather it removed a defense for those who abuse them. There was a lot of benefit to the debate as well, in that many parents started thinking more deeply about how they disciplined their children. Many sought more information on better disciplinary techniques which would improve their parenting skills.

The proposed referendum is mischievous in its intent. The wording does not mention Section 59, it does not provide any solutions to dealing with the “reasonable force” defense which resulted in juries discharging parents who had used severe forms of physical violence. The referendum question shows little interest in the welfare or the rights of children, and that is its biggest failing. Children are not able to speak or advocate for themselves, nor do they have any ability to participate in the law-making process. It is up to us, as adults, to protect those rights and ensure that the vulnerable are kept safe.

—

Anjum Rahman is a founding member of Shama (Hamilton Ethnic Women’s Centre) and the Islamic Women’s Council, as well as being involved with the Hamilton Peace Movement and various interfaith activities. She was a Labour list candidate at the last election, and blogs at The Hand Mirror.

Tags: anjum rahman ,hamilton ,islam ,koran ,muslim ,physical discipline ,physical punishment ,physical violence ,qu'ran ,religion ,religious attitudes to child discipline