July 13, 2009

By Colin James

An enrolment deadline for the yes-means-no/no-means-yes referendum passed on Friday. Have you worked out how to vote? Will you vote?

Why vote? It is only indicative. MPs ignored the 82-92 per cent majority votes in the three previous citizens-initiated referendums, in 1995 on the number of firemen and in 1999 on reducing the number of seats in Parliament and on the needs of victims and minimum and hard labour sentences.

Major-party politicians are not keen to reopen the wounds of 2007 when the Crimes Act defence of reasonable force in disciplining children was abolished. Labour backed Sue Bradford’s bill as an article of faith. National brokered the awkward compromise as an article of politics to avoid losing women’s votes.

Whacking may well be going the way of abortion, settled by a messy compromise in 1977. Abortion still excites the minorities for “choice” and for “life” but it is parked offstage with the Abortion Supervisory Committee.

Two issues are at stake in the whacking/smacking referendum.

One is the value and future of non-binding citizens-initiated referendums.

The hurdle petitioners must clear is high. Parliament’s Clerk must approve the wording and petitioners must get a sample-checked 10 per cent of enrolled electors to sign.

Then petitioners need a credible turnout. This is guaranteed when the referendum runs alongside a general election (as in the two in 1999) or voters see it as important. Turnout in the firemen’s referendum in non-election-year 1995 was a derisory 27 per cent. (Turnout in the compulsory retirement savings referendum in non-election-year 1997 was 80 per cent but that was government-initiated.)

Postal voting, introduced in 2000 and applied to the whacking-smacking referendum, might better the firemen’s 27 per cent. But would even a 90 per cent majority on a 40 per cent turnout in next month’s referendum be convincing? Opponents of MMP questioned the validity of the 54 per cent majority on an 85 per cent turnout in that government-initiated referendum.

Turnout is one objection opponents raise against making citizens-initiated referendums binding (as they are in many United States states and in Switzerland). The topic’s public policy importance is another: the firemen vote was an issue for phone-in polling, not one in which most citizens felt they had a real stake.

Comprehensibility is a third test: can the question be answered by yes or no, can voters be effectively educated so they can make an informed decision and is the question clear? The back-to-front wording of next month’s vote has confused some voters. And so far the educating has been done by protagonists and is most likely to be heard by those voters who themselves have strong views.

That highlights the second issue in the referendum: its substance.

Fact: the police reported on Friday that from October to April they attended 279 child assault “events” which “were most likely to identify ‘smacking’-type incidents”. (The total of child assault “events” was much higher. The new law has not stopped whacking.)

Of the 279, eight involved actual smacking (not whacking) and none of those eight resulted in a prosecution, though four were referred to Child, Youth and Family or a family conference — more than smacking was involved. (Of 39 acts of “minor violence”, eight were prosecuted.)

That doesn’t sound like widespread persecution of good parents who smack.

Most of the referendum debate is at that level: the rights of the child versus parents’ rights. Civilised societies have (slowly, over centuries) been coming to deem that if a child’s rights are abused by parents, society as a whole has a duty to assert the child’s rights.

The whole society has an intimate interest in those rights, as it does of the rights of all “minorities” and defenceless individuals. Social cohesion demands it, as much as ethics. A child belongs to all of society, not just its parents.

But society also has another interest in its children: an economic interest.

A child ill-treated in the womb by a smoking, drinking, poorly-fed mother starts with a handicap. That handicap is made greater by poor nutrition, inattention to cognitive development or violence in the early years of life.

That handicapped child will do poorly at pre-school and school and will be more likely as a teenager to go off the rails or develop mental illness and less likely as an adult to be a productive worker and taxpayer. Worse, that child may as an adult be a charge on society as an addict, beneficiary or criminal or a charge on the state as a prisoner.

Intervening to assure those children a reasonable start is expensive and intrusive. But it is an investment, with a quantifiable return. John Key’s new scientific adviser, Peter Gluckman, has led international work on the science and economics of that.

It is an investment Key has hinted he will make. Whether he does will be a central test of his prime ministership — far greater than a muddled referendum.

- First published in the Dominion Post and Otago Daily Times, July 13, 09

- ColinJames@synapsis.co.nz

July 11, 2009

Three out of four New Zealanders believe the upcoming “anti-smacking” referendum is a waste of money, a survey has found.

The Research New Zealand poll during June of 481 people found 77 percent didn’t support spending money on the non-binding referendum which will cost $8.9m.

Eighteen percent felt it was a good use of taxpayer dollars, while five percent were unsure.

Research New Zealand director Emanuel Kalafatelis said New Zealanders appeared reluctant to spend so much on a referendum during a recession.

“Despite widespread protest about the so-called ‘anti-smacking bill’, it seems Kiwis aren’t willing to spend millions of taxpayers’ dollars on a referendum.”

He said it would be interesting to see how opinions on the cost translated to voter numbers.

Of all the demographic differences in the poll, the only significant difference was between the sexes. Eighty percent of female respondents believed the referendum was a waste of money, compared with 70 percent of male respondents.

July 10, 2009

The latest six-monthly Police statistics confirm that the public can have confidence in the child discipline law and the way it is being administered.

“The statistics released today show that Police have prosecuted fewer cases of smacking and minor physical discipline in the past six months, but more cases of other child assault. In all cases, Police advise that they have only taken action because of the range of circumstances combining to place children at risk. As such, the law is protecting those who need it most and this is positive news,” said Deborah Morris-Travers, spokesperson for the Yes Vote coalition.

These figures continue to demonstrate that Police are exercising the discretion affirmed in the law. While the law grants children the same legal protections as all other citizens have, Police are not prosecuting parents who lightly or occasionally smack their child. The legal opinion from the Human Rights Commission released this confirms the law is a necessary statute and is working well.

“Importantly, the law is consistent with government and community efforts to support parents to do their best for their children through the use of positive, non-violent, parenting techniques.

“The statistics released today affirm what members of the Yes Vote coalition have said many times … the child discipline law is working well and parents have nothing to fear. This is yet another good reason to vote YES in the upcoming referendum,” concluded Ms Morris-Travers.

July 10, 2009

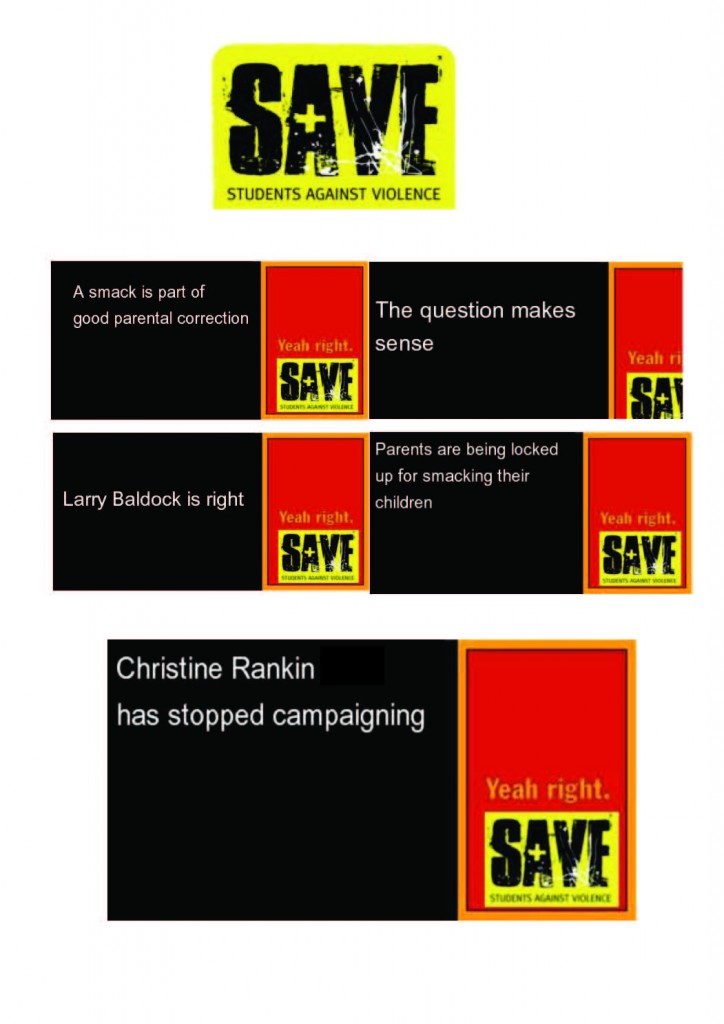

Youth advocates for YES vote have formed a group called Students Against Violence (SAVE) and yesterday launched a set of novel car stickers. One of its organisers, Johny O’Donnell, 15, said the smacking debate was focusing on the rights of parents to hit their children, and overlooked the rights of children not to be hit.

Based in Nelson, they are keen to get other teens on the campaign trail. Contact details are on their website.

July 9, 2009

A group of students campaigning against violence are asking adults to “speak for them” by voting “yes” in August’s smacking referendum according to a story in the Nelson Mail.

Students Against Violence (Save) founding member Johny O’Donnell, 15, said the smacking debate was focusing on the rights of parents to hit their children, and overlooked the rights of children not to be hit.

A student at Nelson College, he told the Mail he was one of five people who turned up to hear long-time child advocate Beth Wood speak on the referendum at the Victory Community Centre.

He said Save intended to have a stand at the Saturday market on the issue. It wanted to do more but was constrained by a lack of funds.

He helped set up Save in Nelson in March as he believed many young people were affected by violence

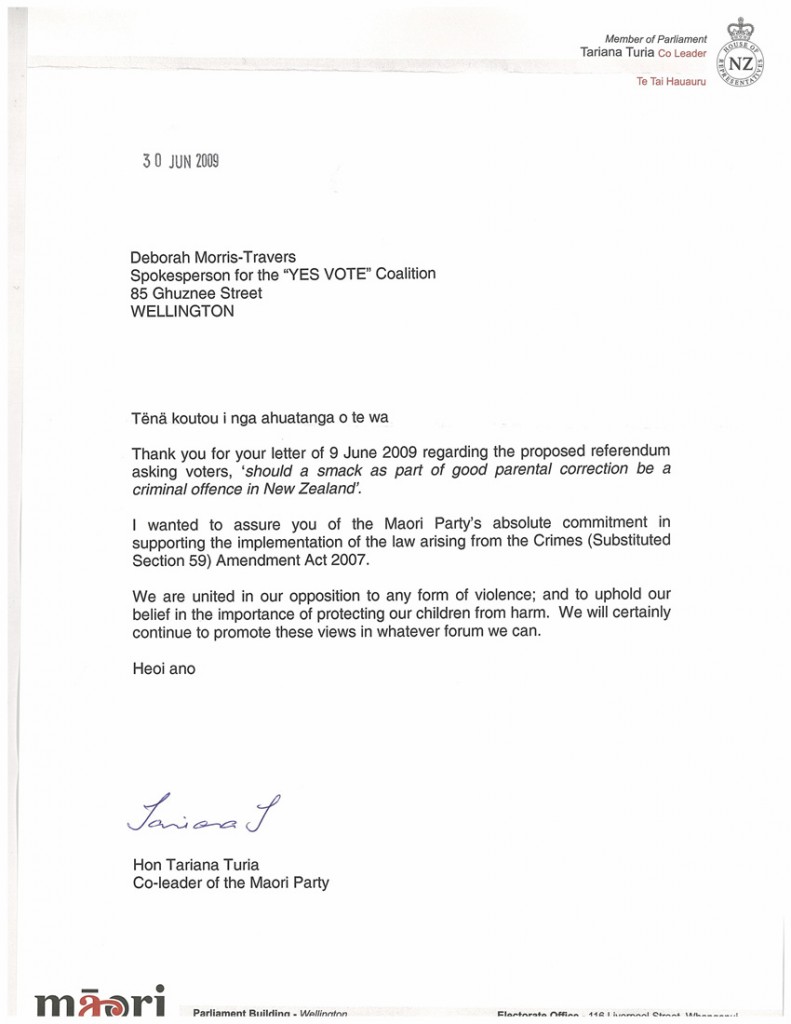

July 9, 2009

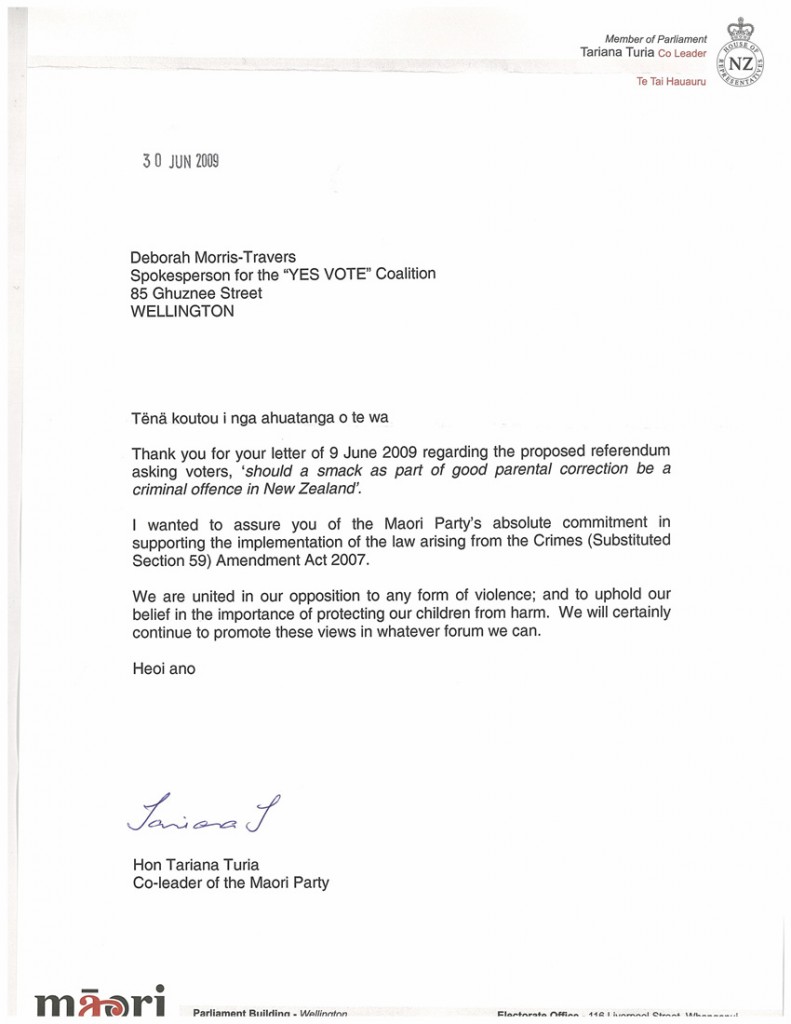

Maori Party supports rights for children and opposes any violence

July 7, 2009

From the Human Rights Commission

A legal opinion prepared by the Human Rights Commission finds that parents have little reason to be concerned that they risk being prosecuted if they give their child a trivial slap or smack.

The Commission has released the legal opinion to help inform debate in the upcoming referendum on the child discipline legislation.

Critics say the new law creates uncertainty for parents. However the legal opinion says the original section 59 of the Crimes Act was no clearer. It said the use of force by parents “by way of correction” was justified if the force was “reasonable in the circumstances.”

Because “reasonable” was open to interpretation, it led to parents being acquitted for disciplining their children with belts, hose pipes and pieces of wood.

Chief Human Rights Commissioner Rosslyn Noonan said, “We’re asking that all those with a genuine concern for the welfare of children and their parents provide accurate information rather than creating unfounded fears on this issue.”

The Commission’s legal opinion says that children may not be hit for the purpose of correction, but states: “Section 59 now allows parents (or someone acting in that role) to use reasonable force for a variety of purposes including the prevention of harm to the child” and to perform the normal daily job of providing good care and parenting.

The amendments gave the police the discretion to prosecute. When receiving a complaint, the police can choose not to prosecute if the offence is considered so “inconsequential that there is no public interest in proceeding with a prosecution.”

The Chief Commissioner said the police have used their discretion wisely and are not prosecuting parents without good reason.

Chief Commissioner Rosslyn Noonan said, “The real issue is that there should be no tolerance for violence against children, even in the guise of parental correction.”

The Human Rights Commission supported the amendments to section 59 because it meant that no longer could abusive parents charged with beating their children hide behind a spurious defence.

And because the amendments are a significant step in making real the human rights and responsibilities set out in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCROC).

Ms Noonan regretted that the referendum question is so flawed that it cannot but provide a meaningless result. “The great shame is that the confusion the question has spawned will result in apathy and cynicism that will undermine still further people’s willingness to participate in New Zealand’s political processes.”

July 6, 2009

The Human Rights Commission is to investigate schools’ anti-bullying policies to see whether children’s rights to safety are being protected according to an article published in Wellington’s Dominion Post (June 6, 09). The move follows calls for a national inquiry by parents of bullying victims at Hutt Valley High School. The investigation is linked to a study by the children’s commissioner into pupil safety and school violence.

Chief Human Rights Commissioner Rosslyn Noonan has agreed to analyse the children’s human rights concerns.

Last December nine Hutt Valley High School boys were dragged to the ground and violated by a pack of six classmates. The victims’ parents wrote to the Human Rights Commission alleging a “systematic failure” by state agencies responsible for protecting children. They asked for a national inquiry into violence and human rights abuses in schools.

July 6, 2009

By Glynn Cardy

Children throughout most of recorded history have been seen as the property of their fathers, similar to women and slaves. It was the father in the ancient Roman world who determined whether a child would live or die. It is estimated that 20-40% of children were either killed or abandoned, with some of the latter surviving as slaves. A child was a nobody unless the father accepted him or her within the family. It was girls who were more often the victims of this rejection.

This is the context for the story of Jesus overriding the objections of his disciples and blessing children. In Mark’s Gospel Jesus takes the children in his arms, lays his hands on them, and blesses them. These are the bodily actions of a father designating a newborn infant for life rather than death, for acceptance not rejection. Scholars think there was a debate going on in the early Christian community about whether to adopt abandoned children, with some leaders staunchly opposed. Mark aligns Jesus with adoption. Jesus was good news for children.

Children in the ancient world were generally viewed negatively. They were physically weak, understood to lack moral competence and mental capability. The Christian notion of original sin as developed by Augustine underlined this negativity and provided the imperative to beat the child in order that it grows up aright. Further, Augustine saw no distinction between a child and a slave. The discipline of slaves had always been more severe than for freeborn, even to the extent of the availability of professional torturers to do such physically demanding work. The doctrine of original sin was bad news for children.

History generally has been bad news for children. In ancient times children in many cultures were victims of ritual sacrifice, mutilation practices, sold as slaves or prostitutes, and were sexually and physically abused. In the Middle Ages abandonment and infanticide were common. It was common too for children as young as seven to be sent away as apprentices or to a monastery. Severe corporal punishment was normative. The apprentice system continued into the 16th and 17th centuries. Although the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance saw changes in how society viewed children, abuse was still common. The Industrial Revolution was also bad news for children. They were made to work in mines, mills, and up chimneys for 14 hours per day – and of course punished if they didn’t work hard enough.

Slowly though changes came. The Enlightenment of the 18th century drew heavily on writers such as Locke and Rousseau. It was an age that challenged the orthodoxy of religion, seeing a child as morally neutral or pure rather than tainted. In response to the wider economic and social changes of the Industrial Revolution there arose a philanthropic concern to save children in order that they could enjoy their childhood. The 20th century understanding of child development evolved in the context of falling infant mortality rates and mass schooling. With these changes also came an emphasis on children’s rights culminating in the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child in 1989.

The Bible generally has been bad news for children too. In the Book of Proverbs we read “He who spares the rod hates his son” (13:24) and again “You shall beat him with a rod and deliver his soul from hell” (23:14). For the most part the Bible is unsupportive of non-violence and children’s rights, or for that matter the rights of women and servants.

Throughout history it has been considered self-evident that all people were not created equal. Only men, particularly those of wealth and high-class, were considered fully human. Women, slaves, servants, and children weren’t. Being less than fully human they belonged to a man. They also needed to be corrected and disciplined by that man or his surrogates. Physically punishing and beating children, women, and servants has been normative for centuries.

Men administering such punishment were not considered to be errant or criminal. From time to time there would be those who acted brutally and cruelly and most societies and religions admonished them for it. In 13th century England, for example, the law read, “If one beats a child until it bleeds it will remember, but if one beats it to death the law applies”. [Albrecht Peiper, Chronik der Kinderheilkunde, Georg Thieme, 1966.]

In this context it is helpful to understand the Crimes (Substituted Section 59) Amendment Act 2007 as deleting an escape clause for the brutal and cruel. The question in the upcoming referendum, whether a smack should be a part of good parental discipline, however raises the broader issue of the acceptability of New Zealand’s culture of physical punishment of children.

Those who administered the violent correction in times past were usually thought to be well-meaning and understood their actions to be a necessary part of their responsibilities. In times past supposedly well-meaning men thought they were entitled to physically discipline their strong-willed wife. Likewise in times past many masters thought beating an uppity servant was necessary. When the laws changed preventing such things the husbands and masters decried the loss of their rights. Likewise this upcoming referendum is a cry from those well-meaning adults who see their right to use violence on their children being eroded. in New Zealand we are in the midst of a cultural change. It is similar to the change regarding the rights of women and the rights of slaves and servants. We have ample evidence from paediatricians, child psychologists, and educationalists about the detrimental effects of any violence meted out upon a child by an authority figure. Although society has sought to restrain and punish adults who are brutal and cruel it has also condoned a culture of medium to low level violence towards children.

Christianity has been complicit in this, citing selective texts from the ancient past, and giving them a divine imprimatur. With an adult male God it has implicitly supported all the human male ‘gods’ in their homes and workplaces to the detriment of others. With the destructive doctrine of original sin the Church has harshly dealt to children and other supposed inferiors. Yet the only texts Christianity has regarding children and Jesus show its founder to be unfailingly kind, compassionate, and non-violent. He never smacked anyone.

From the practice of spirituality many Christians have learnt that what they do to others in effect they do to themselves. The kindness offered to others does something to one’s own soul. Similarly hitting or hurting others is detrimental to one’s own spiritual well-being. It harms one’s capacity to love.

We know from psychology that one method we humans adopt to minimise the self-harm of being violent towards others is to categorise the recipient of the violence as in some way deserving of it. There are numerous examples of women, gays, and people of non-European races being categorised as intellectually and morally inferior in order to justify the physical or institutional violence meted out upon them.

In recent decades science has discovered the impact of childhood experiences on brain development. Whether an adult is generous and loving is determined not only by their genes, but also by how they have been treated as an infant and young child. When a baby is cuddled, treated kindly, played and laughed with, their brain produces certain hormones. On the other hand when young children live with fear, violence, and insecurity their brain produces excessive levels of different hormones such as cortisol. These hormones influence which pathways develop in their brain – its architecture and the adult’s ability to be kind and considerate or angry, sad and distressed.

Cultural change is always hard work. The evidence for the need to change may be there but we adults like the certainty of what we’ve known. There is a sense of security in replicating the past we know, even when we have been harmed by it. There is also a sense of fear that the unknown future may be detrimental to our family and us. Will our children prosper, respect and love us when we raise them without the threat of physical harm?

There is overwhelming evidence that violence has the capacity to change relationships and individuals for the worse. All violence produces fear, and fear is the antithesis of love. We have stopped sanctioned beatings in prisons, psychiatric hospitals, workplaces, and schools, and towards wives and partners. History is changing. Children, maybe the most vulnerable of all the vulnerable, are last. The real question with the upcoming referendum is do we have the courage to create a violence free society?

- Archdeacon Glynn Cardy is vicar of St Matthew-in-the-City, Auckland