Posts Tagged cyf

June 19, 2009

Family First are determined to prove that investigations and prosecutions in cases where there are suspicions of assaults on children are unwarranted and that good parents are being prosecuted because of the child discipline law. Unfortunately the information they give about the cases is not enough to make a judgement about whether or not action was warranted. Neither Police nor CYF will release information on cases. Media reports and court proceedings sometimes provide information but in reality few cases are getting to court. What Family First provide seem to be stories as told by people who are being investigated for ill-treatment of their children and not verified by independent assessment.

In the referendum question that Family First regards as valid the standard set for acceptable assault seems to be a “smack”. This definition does not address questions such as how hard, whether an implement was involved, on what part of the body, at what age, how often and administered by whom? These could all be relevant questions when considering whether a “smack” might compromise a child’s safety and sense of security.

Both the Police and CYF are required to investigate reports of alleged harm to a child and so they should. Any such reports could mean that the child is at risk. Whether there is further action after an investigation requires careful consideration of the facts. These facts could include type of force used, degree of force used, part of body affected, presence or otherwise of injury, age of child, circumstances of the harm inflicted, family history of violence and attitude of the adult(s) involved.

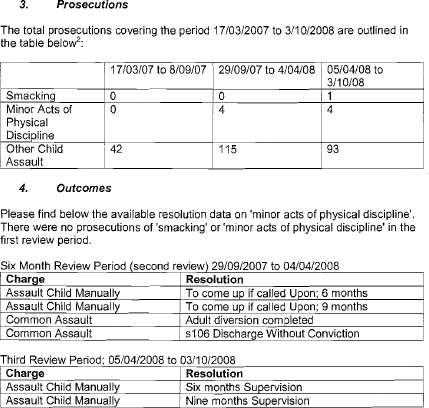

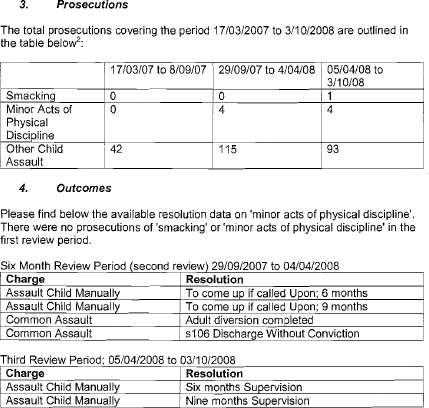

The Police data Family First claim to have obtained under OIA, most of which had already been published, unfortunately gives no detail about the kind of assaults involved. In the past Family First have defended the behaviour of parents whose actions have subsequently been found to be quite abusive. It is reasonable to assume that “smacking” and minor acts of physical discipline, refer to cases where section 59 might have been used as a defence (successfully or unsuccessfully) before law change. Even if there is a valid concern that it might have been obvious to the Police that these cases were low enough on the scale of violence not to warrant investigation nine cases is not a huge number – nothing like the flood of good parents being prosecuted we were warned by Family First to expect.

The third category used in police data is “other child assault”. This refers to more and heavy handed assaults and complex circumstances that no one could find reasonable or acceptable and are likely to have been prosecuted under the old law.

The sensible and compassionate sentences (called weak resolutions by Family First) imposed in the cases that have gone through court and been found guilty do not indicate that the judge took the matter lightly. It is more likely that judges have understanding of the need to set standards in law at the same time as avoiding unnecessary hardship on families.

In examining the details of the cases where investigations are reported to have taken place we must keep in mind the natural tendency of people accused to minimise their own wrongdoing and present their own side of the story. As previously stated verification of the stories is not provided and in any case on the face of it much of the adult behaviour reported seemed to indicate a problem existed.

The only real conclusions we can draw from the material provided by Family First is that there is interest in the community in reporting apparent ill-treatment of children which is a good thing, and that appropriate investigations are taking place.

- Family First’s police report:

June 12, 2009

In a feature article in today’s DomPost entitled The smacking debate needs some correction Bob McCoskrie of Family First makes a number of claims that warrant comment.

This is a continuation to our previous article on misleading claims.

Misleading claim 10: Mild physical punishment does no harm.

Our response: Physical punishment can be harmful, and is at best ineffective in modifying children’s behaviour.

Whether or not mild physical punishment harms is likely to depend on the circumstances it is administered in. The relevant question is does physical punishment do any good? Research indicates that it does not. People continue to strike their children in the name of behaviour correction for historical reasons. It’s time to pay attention to the relevant research and move on to more effective parenting techiques.

The fact that there may be little evidence that minor forms of physical discipline harm children in no way justifies the use of physical discipline. Does punishment, the infliction of pain and retribution really contribute positively to human development and shape behaviour constructively?

A smack is a violent act. If someone smacks an adult woman, do we ask “Does it do her any harm?” Of course not. We assume that to some degree it is harmful emotionally and harmful of her relationship with the person hitting her. It is also an affront to the woman’s integrity. Yet this very question, “Does it do them any harm?” is frequently asked in relation to hitting children.

Misleading claim 11: There has been an increase in child abuse in Sweden since physical punishment was banned there.

Our response: Sweden has been very successful in reducing child physical abuse. Raising awareness of the issue and mandatory reporting have caused reported rates to rise.

In fact there has been a steady decrease in assaults on children since the law changed in Sweden. In Sweden as in other countries increases in notifications for child abuse indicate an increased willingness on the part of the community to take action and report assaults on children rather than an increase in abuse.

Misleading claim 12: Huge increases in notifications to CYF since the law change are in some way connected to the new law.

Our response: The increases are in fact largely due to increases in the number of children referred to CYF by the Police because the children have been present at incidents of domestic violence.

See the Briefing to the Incoming Minister for more information.

Misleading claim 13: The Police have discretion not to investigate cases brought to their attention but CYF do not have discretion.

Our response: Both agencies are required to investigate complaints.

In fact both the Police and CYF are required to investigate cases of assault on children brought to their attention. So they should. The nature of the investigation depends on the information they are given by the person making the complaint.

The Police have discretion not to prosecute which is different from discretion not to investigate. CYF do not prosecute because it is not their function. If they believe prosecution is warranted they refer the case to the Police. In a large proportion of cases CYF take no further formal action following initial investigation, not because there has been no substance to the referral, but because there is thought to be no risk of serious abuse the child. This does not mean all is well in the family, rather that a more supportive and informal solution is indicated eg. referral to a family support agency.

June 4, 2009

The cost of child maltreatment is staggering, yet our willingness to live with the consequences suggests that we remain in a state of denial. The consequences of child maltreatment include:

- Human costs to victims: child fatalities, child abuse related suicide, medical costs, lower educational achievement, pain and suffering.

- Long term human and social costs: medical costs, chronic health problems, lost productivity, juvenile delinquency, adult criminality, homelessness, substance abuse, and intergenerational transmission of abuse.

- Costs of public intervention: child protection services, out-of-home care, child abuse prevention programmes, assessment and treatment of abused children, law enforcement, judicial system, incarceration of abuse offenders, treatment of perpetrators, and victim support.

- Costs of community contributions by volunteers and non-government organisations.

Translating overseas estimates of the costs of child abuse and neglect to the New Zealand context suggests that it imposes long term costs in the vicinity of $2 bn per year, ie in excess of 1% of GDP every year. Roughly one third of this cost relates to dealing with immediate consequences (eg health care, child welfare service, and justice system costs). Another third relates to ongoing health, education, and criminal consequences for child abuse victims in later life. The final third results from a decline in productivity as victims fail to meet their potential.

Reducing the incidence of child maltreatment would not only have a profound impact on the quality of life for potential victims but, by reducing our need to support victims, it will also materially improve the wellbeing of the rest of society.

Prevention is more effective than correction. The main reason for this is that maltreatment has lifelong impacts on the victims. The trauma of maltreatment can inhibit brain development in ways that mars intellectual, communication, social, and emotional abilities. Victims of child abuse face a greater risk of failing at school and of being emotionally alienated from society. That so many victims of maltreatment go on to lead essentially normal productive lives is a testament to the general resilience of human nature. But these victims have done it tough. Life could have been so much better and productive if their formative years had been less stressful. And then there are the walking disaster areas who go on to impose huge costs on themselves and the rest of society.

Abusive behaviour is not constrained by socio-economic status, but research has identified a number of risk factors that increase the potential for child abuse. Key markers of child maltreatment include:

- Parental age and education, eg young or uneducated parents might not be naturally as well equipped to deal with the stresses of parenthood.

- Parental mental health problems such as depression.

- Social deprivation, in particular a lack of wider family support.

- Alcohol or other drug dependency issues.

- Past exposure of parents to interpersonal violence or abuse.

Poverty might exacerbate these pressures, but it is not clear that it is a root cause.

In New Zealand, agencies such as Barnardos, Plunket, Preventing Violence in the Home and many others play a critical role in supporting families to do their best for children.

Also the government’s commitment to preventing child maltreatment has increased considerably in recent years. Child, Youth and Family’s appropriation for education and preventative services for children increased from $16m in the 2004 Budget to $166m in the 2008 Budget. This increased spending has the potential to reduce the incidence and therefore the future cost of child maltreatment. But is it sufficient? Will services provided be effective? And what guarantee have we that the current commitment will be maintained?

A common problem with government sponsored programmes is their top-down, planned design. Large-scale programmes may miss the factors that made small-scale programmes a success or have difficulty obtaining success in different environments. Large programmes also have a propensity for diverting resources away from children and their families into running the bureaucracy and creating an overarching infrastructure.

Large-scale programmes can succeed if they have the following three features:

- The programmes focus on at-risk children and encourage direct parent involvement.

- There is a long term commitment to reducing the incidence of child maltreatment, including changing attitudes about physical punishment.

- The programmes reward successful outcomes in order to encourage high quality and innovative practices.

A way of maintaining commitment would be to create a public endowment that would fund the provision of child and parent support services. A fund would clearly signal an ongoing commitment to reducing the incidence of child maltreatment, a focus on service rather than bureaucracy, a reassurance to service providers that there will be consistent demand for their services, and a willingness to fund effective, specialised and innovative services.

David Grimmond, Senior Economist, Infometrics Ltd

June 3, 2009

Once again the public are being subjected to misleading and expensive Family First advertisements in the Sunday papers. Politicians are being lobbied by Family First who are undermining a law that is working well and want to turn the clock back so that parents can assault children within the law.

In 2007 New Zealand’s law changed to give children the same protection under assault law as other citizens in New Zealand. A provision in the 2007 law reminding parents that police have discretion about prosecution in cases of inconsequential assaults means that very few, if any, cases at the lower end of the smacking/hitting spectrum are being prosecuted.

The law change reflects efforts to end the social acceptability of anyone’s right to hit anyone else. Over time, this will lead to better outcomes for children as fewer children will be exposed to violence.

In their most recent attempt to illustrate that “good” parents are being criminalised Family First cited four cases:

In one case investigations were undertaken and no charges laid. In another the parent was charged and then chose to plead guilty. The sentence is not mentioned. In the third the parent was convicted and discharged without penalty.

In two cases the parents concerned were not convicted (and therefore not criminalised). In the second case the parent pleaded guilty himself. And in the other case a discharge without penalty outcome was a compassionate one that sent a message to the parent and society about non-violence, It did not inflict punishment that could cause hardship to the family involved.

Family First seem to be suggesting that Police and CYF should ignore allegations of assault on children. All reports of assault on children should be investigated – there is good evidence that use of physical punishment is a risk factor for child abuse and although not all physical punishment is child abuse. It is appropriate, that if someone is concerned enough to make a report, that the safety of the child or children involved is investigated. Very few, if any cases, of minor assault are leading to prosecution.

Family First need to clearly state their views on what level of assault on children they find acceptable – does it include blows to the head and face for example or striking a child too young too understand how they should be behaving? Do they regard out of control, bad tempered striking out as appropriate parental correction?

We note that Family First are no longer citing the Jimmy Mason “face-punch” case as evidence that the law is not working, as it has in previous ads, and noted in their own press statement that the conviction was “appropriate”.

Family First are clear that they do not approve of child abuse and urge action to address the real causes of child abuse. But belief in parents’ rights to use physical punishment and belief in its legitimacy as part of child discipline are a real contributing factor to the existence of child abuse. Many children are still beaten because of such beliefs. But Family First do not seem to understand that by sanctioning use of physical discipline they are undermining efforts to reduce abuse.