faq

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why was a referendum held on this issue?

2. Why was that particular question asked?

3. Why did community organisations support a Yes vote in the referendum?

4. Is the referendum binding on the government?

5. Why was the change necessary in the first place? Most parents don’t want to hit their children and only use hitting or smacking as a last resort.

6. Doesn’t the law mean that good parents who give their children a light smack will end up as criminals?

7. Doesn’t this cut across parents’ rights to bring their children up in the way they see fit?

8. Shouldn’t parents just be left to get on with bringing up their own children in the way that best suits them, rather than having nanny-state interference?

9. What was the point in changing the law because parents who abuse children will not stop just because of this legislation?

10. It won’t stop the real abuse that’s out there so shouldn’t we instead be focused on real child abusers and not good parents trying to do a good job?

11. Doesn’t the law create confusion given that Police can use their discretion about whether or not to prosecute?

12. Won’t children grow up spoilt and badly behaved, as the saying goes “spare the rod and spoil the child”?

13. Is it true that most New Zealanders don’t support the legislation, and doesn’t this mean the law needs to be revised?

14. How did the petition organisers get away with formulating such a dishonest question in the first place, and then getting it accepted for a referendum in the second place?

15. What does the law really allow me to do as a parent?

16. Was The Yes Vote Campaign funded by the government?

Do you have a question you would like to ask that is not answered on this page? Please submit it below, and we will consider answering it on the site.

1. Why was a referendum held on this issue?

The referendum was held because a group of people opposed to the current laws protecting children from assault and physical punishment organised a nationwide petition last year which gathered more than 300,000 signatures. This was enough to force a referendum on the issue.

2. Why was that particular question asked?

The question, “Should a smack as part of good parental correction be a criminal offence in New Zealand?” was the question proposed by the petition. Clearly this was designed to ensure that there is an overwhelming “No” vote rather than getting any real understanding of what New Zealanders thought about this issue. The proponents of the referendum hope that this will influence the Government to reverse the law change protecting children. The law, the Crimes (Substituted Section 59) Amendment Act was passed by an overwhelming majority of votes in Parliament in 2007. The law is working well.

The referendum question was a misleading and irrelevant question. The $9m referendum cost was spent at a time when the nation could least afford it. It was a pity that such a large sum was spent in this way instead of providing practical support to parents to enable them to understand the law and provide positive parenting.

3. Why did community organisations support a Yes vote in the referendum?

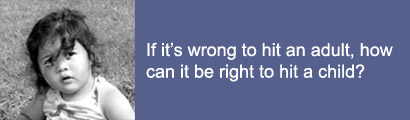

Despite the misleading question, a YES vote will help keep the current law protecting children safe.

A coalition of the leading agencies working with children and families, called The YES Vote strongly believed that children need, and should be given, the same protection from assault and abuse as adults.

New Zealand is a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCROC) which states that:

- all children have the right to protection from discrimination on any grounds

- the best interests of the child should be the primary consideration in all matters affecting the child

- children have the rights to life, survival and development

- all children have the right to an opinion and for that opinion to be heard in all contexts.

Under the previous law New Zealand was not fulfilling its international obligation because the law discriminated against children by not giving them equal protection against assault. It resulted in parents who were charged with seriously assaulting children being acquitted.

4. Is the referendum binding on the government?

No, the referendum is not binding. The law will be subject to a thorough review by the Ministry of Social Development and it is likely the government will pay particular attention to the factual information contained in that review.

5. Why was the change necessary in the first place? Most parents don’t want to hit their children and only use hitting or smacking as a last resort.

Research shows that there are many negative effects associated with children experiencing physical discipline and children in New Zealand still experience harsh or heavy-handed physical discipline. Parents who physically abuse their children often explain their behaviour as discipline. Physical discipline is a known risk factor for abuse. The law change was needed to grant children the same legal protections as other citizens and to make the law consistent with government and community efforts to promote positive, non-violent, parenting.

6. Doesn’t the law mean that good parents who give their children a light smack will end up as criminals?

No, the evidence is that the law is not leading to the criminalisation of good parents.

During the debate about the law change one of the major objections to the removal of the section 59 Crimes Act 1961 statutory defence was that parents who only occasionally smacked a child lightly would be prosecuted and, if convicted, criminalised. The police discretion provision was inserted in the legislation late in its passage through Parliament to provide reassurance on this matter.

A review of six-monthly Police reports indicates that the number of complaints about smacking is very small. There appears to have been some increase in complaints about use of more heavy handed force and some prosecutions. It is appropriate that some action is taken where assaults are heavy handed – although not necessarily prosecution. To suggest that children who are subjected to heavy handed assaults should not be protected is to suggest that their safety is not a paramount consideration.

Claims have been made that the law is resulting in unwarranted investigations into family lives. The cases used to support these claims cannot be verified because Police and CYF information about them is confidential.

7. Doesn’t this cut across parents’ rights to bring their children up in the way they see fit?

No, the only thing that has changed is that children are now protected from physical assault in the same way that adults are. It has never been legal to hit a child but previously the law stated that if a person was charged with assault on a child they could use the Section 59 “reasonable force” defence. This has been used to try to justify extreme forms of physical punishment such as the use of a riding crop and other instruments.

Children have the same rights as adults to protection from physical violence and assault.

8. Shouldn’t parents just be left to get on with bringing up their own children in the way that best suits them, rather than having nanny-state interference?

The role of the government is to enact laws to protect people, and in particular the most vulnerable. Children are amongst the most vulnerable people in any society.

The law identifies a range of situations in which parents may need to use force such as restraining a child in a situation of danger, or when property or another person is at risk. The law acknowledges the need for parents to get on with the job of normal parenting but is explicit that parents should not use force for the purposes of correction.

9. What was the point in changing the law because parents who abuse children will not stop just because of this legislation?

Along with laws protecting children, community organisations are supportive of many initiatives that help promote positive parenting. There is a need for more education about positive parenting and how to bring up children in happy, secure, safe and positive environments. Positive non-violent discipline works well for both parents and children. It is more effective in teaching children to behave well and it improves the outcomes for children.

10. It won’t stop the real abuse that’s out there so shouldn’t we instead be focused on real child abusers and not good parents trying to do a good job?

Unfortunately, there is too much violence in many sectors of New Zealand society and in many of New Zealand’s homes. Having laws preventing physical discipline on children, along with a package of other measures such as educating parents, will all help towards reducing family violence. Using physical punishment is a known risk factor for abuse and we need to work to change attitudes and behaviours over time.

11. Doesn’t the law create confusion given that Police can use their discretion about whether or not to prosecute?

Police discretion on whether to prosecute was inserted in the legislation to help alleviate concerns that parents who lightly hit their child could be criminalised. If police deem the assault to be “inconsequential” then they can use their discretion about whether or not to charge. Reports show that this is working well. Good parents are not being charged with assault over inconsequential assault. There are a many other laws that police can use discretion about whether to charge and no public concern over potential confusion.

12. Won’t children grow up spoilt and badly behaved, as the saying goes “spare the rod and spoil the child”?

All the evidence shows that children who are brought up in secure, non-violent and positive environments are better adjusted, happier and better behaved. They have a much better chance of growing into healthy happy adults.

‘Spare the rod and spoil the child’ is the most quoted biblical endorsement for physical punishment. Yet these words do not appear in any Bible. They are from an anti-Puritan poem by Samuel Butler. The poem is about sex, not child discipline.

13. Is it true that most New Zealanders don’t support the legislation, and doesn’t this mean the law needs to be revised?

Although many New Zealanders do not fully understand the law, because there has been no government-funded campaign to educate people, there is growing support for the law.

In 2008 the Children’s Commissioner, Dr Cindy Kiro, thought it important to establish a benchmark for monitoring knowledge of the child discipline law, attitudes to the law and attitudes about the use of physical punishment. She commissioned the research company UMR to include relevant questions in an omnibus survey.

Key findings included:

- 43 percent of respondents in the independent omnibus survey. supported the law while about one-third opposed it. The remainder was neutral.

- 37 percent clearly oppose the use of physical discipline. Support for the use of physical discipline appears to be declining over time.

- Awareness of the law change is high, although understanding of what the law means, is lower.

- There are relatively high levels of support, at least in principle, for the concept that children should be entitled to the same protection from assault as adults.

When the law was going through parliament many New Zealanders were concerned about the law change because they believed that good parents would be criminalised. That has not happened. The law is working well. As more people understand the law and modern parenting, there is growing support for non-violent methods of raising children. This legislation has given children the same protection from assault as adults. Under the previous law they had less protection than adults and animals and therefore were discriminated against.

The law sets a standard that children should have the same protection from assault as other New Zealanders. In other countries that have changed there laws it has taken time for attitudes and behaviours to catch up with the norm set by the law.

14. How did the petition organisers get away with formulating such a dishonest question in the first place, and then getting it accepted for a referendum in the second place?

The petitioners submitted their question to the Electoral Commission and there were insufficient objections to require the question to be changed. A significant objection was raised by the Ministry of Justice but this was ignored. The question was approved and once 10 percent of registered votes signed the petition there was no going back.

15. What does the law really allow me to do as a parent?

So what does the law really allow me to do as a parent?

Everything you need to do, as long as it doesn’t include using force for the purpose of correcting or punishing your child. Here’s the actual wording:

Every parent of a child and every person in the place of a parent of the child is justified in using force if the force used is reasonable in the circumstances and is for the purpose of:

(a) preventing or minimising harm to the child or another person; or

(b) preventing the child from engaging or continuing to engage in conduct that amounts to a criminal offence; or

(c) preventing the child from engaging or continuing to engage in offensive or disruptive behaviour; or

(d) performing the normal daily tasks that are incidental to good care and parenting.

Parenting can never be strictly ‘hands off’ and as you see the law is very clear parents are totally free to keep their kids safe, out of trouble and to go about normal tasks of parenting and caring for their children.

Sometimes parenting is a hands on process – you hang on to get them into their nappies or out of their coats, you remove them from tormenting the cat or their younger sibling. Imagine all the scenarios that are part of parenting a child, but take away the whacks and wallops. The whole intent of the law:

‘to make better provision for children to live in a safe and secure environment free from violence by abolishing the use of parental force for the purpose of correction.’ Elsewhere on this site you’ll find background information on positive discipline as well as tips on positive parenting.

16. Is The Yes Vote Campaign funded by the government?

No, we are not government funded.

The Yes Vote Coalition comprises the major child and family-focused non-government organisations (NGOs) listed on the About Us page, and is supported by a large and growing number of highly respected community organisations and individuals, including leaders of major faiths and Christian denominations who favour the law that is in place now.

Most of the day-to-day work in running The Yes Vote Campaign is performed by independent volunteers, although some staff time is donated to the campaign by supportive NGOs. The NGO’s advocacy functions are funded from sources other than Government contracts. The campaign itself is funded by donations and private philanthropic funders that support the law. The Yes Vote Campaign will file a return of expenses with the Chief Electoral Office following the referendum.

Speaking for the volunteers, we’re just normal people, mostly parents, who are taking a huge chunk of time out of our lives to devote to this important campaign. Wanting the law to say that hitting a child is wrong is just a no-brainer for us.

Do you have a question you would like to ask? Please submit it below, and we will consider answering it on the site.

[contact-form]